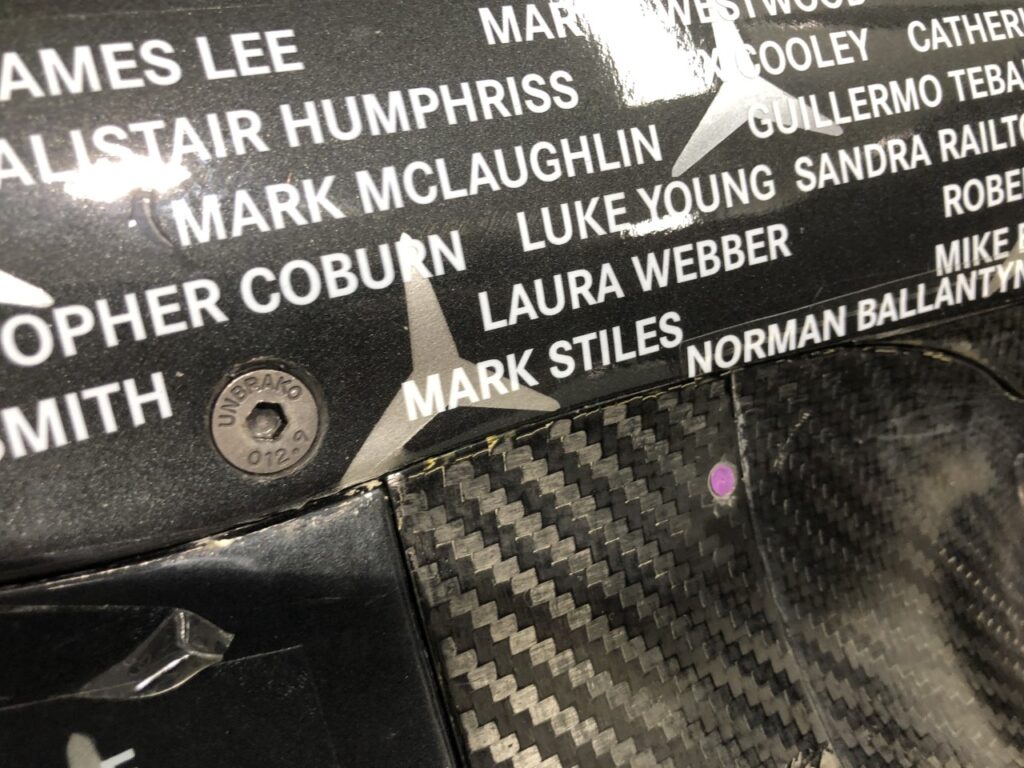

Welcome to our first “Motorsport starts with RC cars” segment! In this inaugural instalment, a familiar name and face from the world of on-road racing in BRCA and EFRA circles: Mark Stiles!

Mark has been able to take his RC hobby interest and build it up to attain what many would call a dream job: working in Formula One! And not just any old team: Mark works for the multiple World Championship-winning Mercedes AMG Petronas F1 team!

How did this happen? and how might you be able to take your RC hobby and interests into a similar direction? Read on to find out!

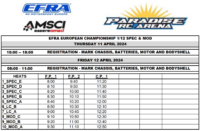

EFRA: Hello Mark! Thanks so much for taking the time to talk with us.

Mark: Hello! Thanks for asking.

A lot of people in UK RC and especially on the 1/12th Nationals racing circuit know your name, but if you had to describe yourself in a Tweet-length description, what would you say?

I’m an outspoken and sometimes opinionated person who has a competitive nature and a passion for motorsport and racing. I like my food, enjoy a drink and cherish the company of like-minded people. I find it rewarding and satisfying to see others enjoy themselves or improve with my help, but I am also proud of my own accomplishments.

So let’s dive into this and start at the beginning, shall we? First question: what first got you interested in motorsports?

I grew up around cars and motorsport; in some households there’s a passion for football, rugby or other mainstream sports, but for me it has always been motor racing. My father was a car and motor sport enthusiast so some of my earliest childhood memories are of attending car shows/exhibitions, races, rallies and other events with him and watching motor sport on TV. I guess you could say that racing is in my blood and it was my dad who nurtured and encouraged my interest as I got older.

I think many of us can relate to that! And how about RC, how did you get started in the hobby?

My foray into the world of RC Car Racing should be credited to one of my schoolteachers. Shortly after starting secondary school (so I’d have been about 12 years of age) I came to know about a club that my first Design & Technology teacher ran. It was an RC Car Club that ran after school on Wednesdays, but there was also a weekly race event held on a Friday lunchtime. I wandered in off the playground one Friday lunchtime, saw these little cars whizzing around on the carpeted area in the D&T department and immediately decided that I wanted to get involved and have a go. The cars we raced were out of the box Mardave V12’s with basically no modifications permitted to keep it simple and cheap. The format was simple; a single 5-minute heat with the overall results based on most laps completed in the time. I won first time out, so it snowballed from there really. A couple of the other kids who raced at school ended up finding a local club which happened to race the same cars, so I went along one evening and the rest, as they say, is history!

In a broader sense, RC Car Racing can provide a social setting in which you can gain experience of being in a competitive environment, dealing with pressure, collaborating with teammates and being fair and respectful towards others.

So, it’s obviously very, very cool to work with the Formula One team that’s dominated the top category of racing cars for the past several years. So let us know: what is it that you do there? What’s your role there and what’s a ‘day in the office’ like for you?

In regards to my role at Mercedes F1, I am a Composite and Mechanical Design Engineer. Most of my work is done using CAD (Computer Aided Design) software to design brake ducts, heatshields and suspension components for the F1 car. This will typically involve taking a surface (or “shape”) that has been developed in the wind tunnel or CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) and designing the supplied shape into individual panel or component designs that can be manufactured, assembled onto the race cars and used for their intended purpose.

In addition to the part design, I will usually design all of the moulds and associated tooling, jigs, etc., to enable the parts to be manufactured. I am also responsible for the successful and reliable use and performance of the parts I design, so I have direct involvement with the development, manufacture and use of my car area. On a current F1 car there are in the region of 400 individual drawings that make up a single brake duct assembly; that figure includes everything from the most basic of mould tools right up to the completed assembly drawing.

Wow! 400 drawings just for a brake duct… That’s incredible. And how did you get into that position with Mercedes F1? How did you build up your skillset to get where you are now?

As far as “how I got here” is concerned, it has really been a case of learning and developing my skills and experience as I go. Before designing parts that go onto the race cars, I have previously worked at other F1 teams in other roles such as manufacturing and machine tool programming and wind tunnel model design. Formula 1 is a very fast-paced environment to work in, so you learn quickly and often end up being involved with a diverse range of projects. I have found that once you’ve got some specialist experience in F1 (in whatever role it may be) you become very employable as there are few industries which operate at such a fast pace in a technological field.

Yes, definitely, you’re literally on the bleeding edge of tech, which is a really desirable place to work for many people. Just look at at the listings on Motorsport Jobs to see the kind of skills needed to get a look in at the positions listed there!

So apart from custom fabricating parts for your 1/12th racer, what kind of skills transference do you notice from your own point of view between full-size racing and scale racing?

There are obviously transferable skills between RC Racing and full-sized motorsport and vice versa. The obvious ones are the understanding and use of vehicle dynamics and car setup knowledge as well as physically working on the cars (you’d be surprised how many engineers there are who have very little experience of actually building anything and understanding how to operate and maintain it!).

However, I think one of the biggest things that can be learnt from RC Racing that feeds into full sized racing is a basic understanding of racing car architecture and terminology. In layman’s terms this means “what things are called, what they usually look like and how they work”. It was RC Car Racing that offered me an insight into how suspension operates, what a transmission system does, how electrical energy can be stored and then used to power a vehicle or system. I have on many occasions referred to RC Racing as “Motorsport In Miniature”, because that’s basically what it is. It is obtaining a grasp of those basic principles that enables you to develop a far deeper and broader understanding, not just of racing cars but of everything that we have and use in our daily lives.

In a broader sense, RC Car Racing can provide a social setting in which you can gain experience of being in a competitive environment, dealing with pressure, collaborating with teammates and being fair and respectful towards others. These are all things that simply cannot be taught in a classroom or learnt from the internet and my exposure to them in RC Racing was undoubtedly helpful to me in both my career and personal development.

I wrote over 100 letters to various racing teams and

motorsport companies in the UK. Everywhere from F1 Teams to

proprietary part manufacturers and everything in between.

From a career perspective, how would you describe your journey from model car fan/collector/racer to ‘F1 car designer’? What was your particular route in school, qualifications, job positions, etc.?

I had my sights set on a career in motorsport from a very young age (possibly 8 or 9 years old). At that age a lot of kids want to become professional sportspeople, pop stars, actors, perhaps even vets or work in the armed forces. I think that’s because they see something that looks fun or that interests them and that is what they want to do. Of course, a part of me would’ve liked to be a racing driver, but I also had quite a deep-rooted interest in the reasons why racing cars look as they do and a desire to understand how they work. I was good at maths and science in school and was also quite capable from a practical point of view.

What really helped me in school was already having an ambition or goal; it allowed me to plan my pathway and I became very focused on what I wanted to do and how I was going to get there. That is not to say that children must decide on their desired career paths so early in life, but I think it helps to have an interest in a particular field or profession as it help you to make informed choices about what subjects to study and experience to try and get along the way.

I took quite a normal route through school in the UK by studying for GCSE’s and then A-Levels, though as mentioned above the subjects I chose at each stage had a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics) bias. I picked Physics, Maths and Product Design at A-Level as those subjects were required to study engineering at university.

My university degree is in Motorsport Engineering (BEng), which is essentially Mechanical Engineering but with a motorsport focus. I did what is known as a “sandwich course”, so after completing the first two years of study I worked in industry for 12 months before then completing my final year of university study. My industrial placement was not working in motorsport; instead I was a production line fault data analyst for BMW Mini. At the time I felt a little bit despondent as being sat in an office looking at car production line faults and producing charts and tables in Excel seemed very much removed from where I wanted to end up. There were no racing cars, there was no competition and it wasn’t an engineering role. I later realised though that I was learning workplace skills and getting work experience that I would not have otherwise obtained. In fact, the person who hired me for my first job in F1 later told me that I wouldn’t have been shortlisted for interview had I not completed an industrial placement as part of my university degree course. The lesson for me in that instance was that nothing you do is pointless and even the most obscure or irrelevant seeming experiences are never wasted.

What really helped me was having an ambition or goal;

it allowed me to plan my pathway and I became very focused

on what I wanted to do and how I was going to get there.

Upon finishing university, I needed to find my first job, so I wrote over 100 letters to various racing teams and motorsport companies in the UK. Everywhere from F1 Teams to proprietary part manufacturers and everything in between. After several weeks of waiting I received just one reply from a company that wanted to invite me to an interview for a graduate engineering position. I later found out that I was one of just 3 successful candidates chosen from over 120 applicants. To this day I consider myself very fortunate to have been offered such an opportunity, but it is also true to say that it was the culmination of so many years of hard work and focus. The company was McLaren, and so started my journey into a Formula 1 Engineering career.

I spent 2 years as a graduate engineer at McLaren where I worked as a production engineer. I programmed CNC milling machines and designed simple jigs and fixtures to assist with the manufacture of car parts and mould tooling whilst also helping to implement processes and procedures to streamline the manufacturing processes and make the production operations in the factory more efficient.

I was keen to work in more of a design-based role, so I then joined Toro Rosso to work at their wind tunnel in the UK as a wind tunnel model design engineer. Whilst being a part of an F1 team, this was very different to what I had enjoyed at McLaren. After 2 years, whilst contributing directly to the development of an F1 car, I hadn’t seen and touched a full sized one in the flesh. F1 wind tunnels cannot be any larger than 60% scale, so it wasn’t a “real” car that I was designing parts for. I yearned for the feeling I got at McLaren where the whole team was in the same factory and I would walk past the race cars on my way into the office each morning. It’s not until you are without things like that you realise how valuable they are as motivators, and a reminder of why you’re there.

I then joined Lotus, which later became Renault at their base in Enstone, UK. Initially I did the same job there as I did at Toro Rosso, but I soon found it to be a much more inspiring environment and more in tune with what I thought working in F1 should be like. Enstone is a purpose built, standalone F1 factory and whilst not as plush or swanky as McLaren, there is a definite sense of spirit and purpose there. After about 6 months I was seconded to the race car design office to assist with some composite mould tool design for parts that would be made for the forthcoming years car. In short, I never went back to the wind tunnel and was offered my secondment role on a permanent basis. Some months later I then became responsible for design of the rear brake duct assembly on the car, a role that I subsequently worked in for almost 3 further years.

In 2017 I made contact with a colleague who had previously left Renault to join Mercedes and he informed me that they were looking to recruit someone for a role that was ideally suited to my skills and experience, so I submitted an application. After 2 gruelling interviews lasting almost 3 hours each, I was offered the job and I started work at Mercedes in the winter of 2017.

Since joining Mercedes AMG Petronas F1, my main role has been to lead the design of the rear brake duct assembly, but my work has also diversified and I’ve designed wheels, other suspension components and more recently some electrical enclosures and heatshields that are fitted around the power unit. Mercedes is a very big team with over 1000 employees, but my work there is more varied than it was at the other teams I’ve worked for. They encourage engineers to gain exposure to all areas of the car and develop to become more rounded engineers, possibly even future leaders within the company. Despite the unprecedented success achieved in recent years, the team remains humble and is careful to no become complacent.

That really is quite the journey, and it’s fascinating to see how all the schooling and jobs you’ve had have led to where you are now.

I wandered in off the playground one Friday lunchtime, saw these little cars whizzing around on the carpeted area and immediately decided that I wanted to get involved and have a go.

Oh yes, the social aspect of a competitive community can’t be over-stressed, so we totally agree. It’s wonderful to see teams of racers, whether grouped by family, friends, brand sponsor or country gathered together to race against each other but still laughing and smiling – or even better – grouped around one car or pit area to get something critical fixed just before a race. It’s that teamwork that brings people together!

For the last several years (at least, pre-pandemic), you’ve been one of the top 1/12th scale racers in the UK, representing the UK at the Euros and even writing review articles in magazines – is RC your only hobby outside of work and family, or are there other interests that take up some of your time?

For a long time (nearly 20 years) RC Racing has been my only serious hobby. Like many kids I participated in sports for school and local teams, but I was never as invested in (or as good at!) them as I was at RC Racing, so RC Cars was the thing that stayed with me throughout my teenage years and into adulthood. There aren’t many competitive activities or sports in which you can compete at national or international level for such an affordable investment in both money and time. RC Racing is very accessible and inclusive in that respect; it does not discriminate against age, sex, ethnicity, athletic or physical ability and in fact it should be encouraged as a great way for people who have physical or mental impairments to socially interact and compete on a level playing field.

2020 was a year that we’ll remember for a very long time… what did you get up to instead of club racing and hitting the Nationals circuit?

In recent years I have developed an interest in road cycling. I have ridden socially with a local club for a few years and during 2020 I ended up doing over 8000km in 12 months. I don’t compete in anything more than occasional small club level events, but I’ve managed to lose some weight and build up a reasonable level of fitness in the last year or so. That said, one of the main reasons I do it is so that I can drink coffee and eat cake! It’s a great way to branch out socially, see the local countryside and stay healthy in body and mind. It doesn’t offer the same level of competition and exhilaration as a close fought RC Race though, so I’m looking forward to doing some of that again soon!

In recent years I have developed an interest in road cycling. I have ridden socially with a local club for a few years and during 2020 I ended up doing over 8000km in 12 months. I don’t compete in anything more than occasional small club level events, but I’ve managed to lose some weight and build up a reasonable level of fitness in the last year or so. That said, one of the main reasons I do it is so that I can drink coffee and eat cake! It’s a great way to branch out socially, see the local countryside and stay healthy in body and mind. It doesn’t offer the same level of competition and exhilaration as a close fought RC Race though, so I’m looking forward to doing some of that again soon!

Cycling certainly does have a lot of crossover with full-size and scale motorsport guys – it must be all the engineered bits, carbon and aluminium…

EFRA has turned a corner now,

Javier brings fresh enthusiasm and impetus.

EFRA has made big strides in the past few years, trying to get the word out to the public and ‘people on the street’ about how cool RC cars are, with an eye to getting them into the hobby. What do you think of their recent efforts? What do you think they could improve?

It’s great to see EFRA taking a more positive approach to the promotion of RC Motorsport and it is clear that they are working hard to develop a strategy which enables them to showcase RC Racing to the general public, especially young people.

In the past EFRA has been viewed as a bit of an “old man’s club” that is run by people who aren’t very well engaged with the latest technology and trends. I used to pay my annual EFRA license fee to race at the European Championships, and beyond that it wasn’t particularly clear how my subscription was being used or indeed what EFRA was doing for the RC hobby.

I think it’s turned a corner now though; the new EFRA chairman Javier Garcia brings fresh enthusiasm and impetus. There has been some re-branding work going on recently and there has been a noticeable improvement in how EFRA engages with its members and the wider community. I hope things go from strength to strength in the coming years.

EFRA is an international federation, so I’m not entirely sure whether they are well placed to help individual clubs. Personally, I see EFRA as being more of an umbrella organisation that should be one of the public-facing sides of RC Motorsport. EFRA should draw people into the hobby with general promotion and marketing and then direct them towards the national federations, who in turn should connect people to clubs and regionally based competitions and events. Show newcomers the first rung of the ladder and make it as easy as possible for them to climb it if they wish.

The only way that I can see for EFRA to assist clubs directly is with the provision of guidance, advice and possibly even personnel to help organise and run EFRA sanctioned events. It is a shame to see an event that is well organised and run followed by a poor one because the organising club do not have the experience and expertise to make it a successful event. EFRA should draw upon the skills, experience and support of its members and associates with the aim of making events consistently good, wherever and whenever they are held.

Thank you so much for your time, Mark! It’s been fascinating to see how the RC hobby really can lead to a real dream job!